Laurel and Hardy were a comedy double act during the early Classical Hollywood era of American cinema. The team was composed of English thin man Stan Laurel (1890–1965) and American fat man Oliver Hardy (1892–1957). They became well known during the late 1920s through the mid-1940s for their slapstick comedy, with Laurel playing the clumsy and childlike friend of the pompous bully Hardy.]The duo's signature tune is known variously as "The Cuckoo Song", "Ku-Ku", or "The Dance of the Cuckoos". It was played over the opening credits of their films and has become as emblematic of the duo as their bowler hats.

Prior to emerging as a team, both actors had well-established film careers. Laurel had appeared in over 50 films while Hardy had been in more than 250 productions. The two comedians had previously worked together as cast members on the film The Lucky Dog in 1921. However, they were not a comedy team at that time and it was not until 1926 that they appeared in a movie short together, when both separately signed contracts with the Hal Roach film studio. Laurel and Hardy officially became a team in 1927 when they appeared together in the silent short film Putting Pants on Philip. They remained with the Roach studio until 1940 and then appeared in eight "B" movie comedies for 20th Century Fox and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer from 1941 to 1945.[ After finishing their movie commitments at the end of 1944, they concentrated on performing in stage shows and embarked on a music hall tour of England, Ireland, and Scotland. In 1950, before retiring from the screen, they made their last film, a French/Italian co-production called Atoll K.

They appeared as a team in 107 films, starring in 32 short silent films, 40 short sound films, and 23 full-length feature films. They also made 12 guest or cameo appearances that included the Galaxy of Stars promotional film of 1936. On December 1, 1954, the pair made one American television appearance when they were surprised and interviewed by Ralph Edwards on his live NBC-TV program This Is Your Life. Since the 1930s, the works of Laurel and Hardy have been released in numerous theatrical reissues, television revivals, 8-mm and 16-mm home movies, feature-film compilations, and home videos. In 2005, they were voted the seventh-greatest comedy act of all time by a UK poll of fellow comedians. The official Laurel and Hardy appreciation society is known as The Sons of the Desert which was named after a fictitious fraternal society featured in the Laurel and Hardy film of the same name.

Early careers

Stan Laurel

Stan Laurel (June 16, 1890 – February 23, 1965) was born Arthur Stanley Jefferson in Ulverston, Lancashire (today Cumbria), England into a theatrical family. His father Arthur Joseph Jefferson was a theatrical entrepreneur and theatre owner in northern England and Scotland who, together with his wife, was a major force in the industry. In 1905, the Jefferson family moved to Glasgow to be closer to their business mainstay of the Metropole Theatre, and Laurel made his stage debut in a Glasgow hall called the Britannia Panopticon one month short of his 16th birthday. Arthur Jefferson secured Laurel his first acting job with the juvenile theatrical company of Levy and Cardwell, which specialized in Christmas Pantomimes.]ng actor, and as an understudy for Charlie Chaplin.Laurel said of Karno, "There was no one like him. He had no equal. His name was box-office."[In 1912, Laurel left England with the Fred Karno Troupe to tour the United States. Laurel had expected the tour to be merely a pleasant interval before returning to London; however, he migrated to the U.S. during the trip.[ In 1917, Laurel was teamed with Mae Dahlberg as a double act for stage and film; they were living as common law husband and wife.[ The same year, Laurel made his film debut with Dahlberg in Nuts in May. While working with Mae, he began using the name "Stan Laurel" and changed his name legally in 1931.[ Dahlberg held Laurel's career back because she demanded roles in his films, and her tempestuous nature made her difficult to work with. Dressing room arguments were common between the two; it was reported that producer Joe Rock paid her to leave Laurel and to return to her native Australia.[ In 1925, Laurel joined the Hal Roach film studio as a director and writer. From May 1925 until September 1926, he received credit in at least 22 films. Laurel starred in over 50 films for various producers before teaming up with Hardy.[ Prior to that, he experienced only modest success. It was difficult for producers, writers, and directors to write for his character, with American audiences knowing him either as a "nutty burglar" or as a Charlie Chaplin imitator.[

Oliver Hardy

Oliver Hardy (January 18, 1892 – August 7, 1957) was born Norvell Hardy in Harlem, Georgia. By his late teens, Hardy was a popular stage singer and he operated a movie house in Milledgeville, Georgia, the Palace Theater, financed in part by his mother. For his stage name, he took his father's first name calling himself "Oliver Norvell Hardy" while offscreen his nicknames were "Ollie" and "Babe". The nickname "Babe" originated from an Italian barber near the Lubin Studios in Jacksonville, Florida who would rub Hardy's face with talcum powder and say "That's nice-a baby!" Other actors in the Lubin company mimicked this and Hardy was billed as "Babe Hardy" in his early films.Seeing film comedies inspired an urge to take up comedy himself and, in 1913, he began working with Lubin Motion Pictures in Jacksonville. He started by helping around the studio with lights, props, and other duties, gradually learning the craft as a script-clerk for the company.[ It was around this time that Hardy married his first wife Madelyn Salosihn. In 1914, Hardy was billed as "Babe Hardy" in his first film, Outwitting Dad. Between 1914 and 1916 Hardy made 177 shorts as Babe with the Vim Comedy Company that were released up to the end of 1917. Exhibiting a versatility in playing heroes, villains and even female characters, Hardy was in demand for roles as a supporting actor, comic villain or second banana. For 10 years he memorably assisted star comic and Charlie Chaplin imitator Billy West, Jimmy Aubrey, Larry Semon, and Charley Chase. In total, Hardy starred or co-starred in more than 250 silent shorts of which roughly 150 have been lost. He was rejected for enlistment by the Army during World War I due to his size. In 1917, after the collapse of the Florida film industry, Hardy and his wife Madelyn moved to California to seek new opportunities.

History as Laurel and Hardy

Style of comedy and characterizations

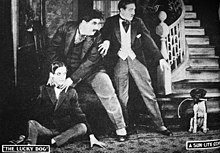

Laurel and Hardy in The Lucky Dog (1921)

Stan Laurel was of average height and weight, but appeared small and slight next to Oliver Hardy, who was 6 ft 1 in (185 cm) tall and weighed about 280 lb (127 kg) in his prime. They used some details to enhance this natural contrast. Laurel kept his hair short on the sides and back, growing it long on top to create a natural "fright wig". At times of shock, he would simultaneously cry while pulling up his hair. In contrast, Hardy's thinning hair was pasted on his forehead in spit curls and he sported a toothbrush moustache. To achieve a flat-footed walk, Laurel removed the heels from his shoes. Both wore bowler hats, with Laurel's being narrower than Hardy's, and with a flattened brim. The characters' normal attire called for wing collar shirts, with Hardy wearing a neck tie which he would twiddle and Laurel a bow tie. Hardy's sports jacket was a tad small and done up with one straining button, whereas Laurel's double-breasted jacket was loose fitting.

A popular routine the team performed was a "tit-for-tat" fight with an adversary. This could be with their wives—often played by Mae Busch, Anita Garvin, or Daphne Pollard—or with a neighbor, often played by Charlie Hall or James Finlayson. Laurel and Hardy would accidentally damage someone's property, with the injured party retaliating by ruining something belonging to Laurel or Hardy. After calmly surveying the damage, they would find something else to vandalize, and conflict would escalate until both sides were simultaneously destroying items in front of each other. An early example of the routine occurs in their classic short, Big Business (1929), which was added to the National Film Registry in 1992. Another short film which revolves around such an altercation was titled Tit for Tat (1935).

One best-remembered dialogue was the "Tell me that again" routine. Laurel would tell Hardy a genuinely smart idea he came up with, and Hardy would reply, "Tell me that again." Laurel would attempt to repeat the idea, but babble utter nonsense. Hardy, who had difficulty understanding Laurel's idea even when expressed clearly, would understand perfectly when hearing the jumbled version. While much of their comedy remained visual, various lines of humorous dialogue appeared in Laurel and Hardy's talking films. Some examples include:

- "You can lead a horse to water but a pencil must be led." (Laurel, Brats)

- "I was dreaming I was awake but I woke up and found meself asleep." (Laurel, Oliver the Eighth)

- "A lot of weather we've been having lately." (Hardy, Way Out West)

Rather than showing Hardy suffering the pain of misfortunes, such as falling down stairs or being beaten by a thug, banging and crashing sound effects were often used so the audience could visualize the scene for themselves. The 1927 film Sailors Beware was a significant film for Hardy because two of his enduring trademarks were developed. The first was his "tie-twiddle" to demonstrate embarrassment.[ Hardy, while acting, had been met with a pail of water in the face. He said, "I had been expecting it, but I didn't expect it at that particular moment. It threw me mentally and I couldn't think what to do next, so I waved the tie in a kind of tiddly-widdly fashion to show embarrassment while trying to look friendly." His second trademark was the "camera look" in which he breaks the fourth wall.Hardy said: "I had to become exasperated so I just stared right into the camera and registered my disgust."[ Offscreen Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy were quite the opposite of their movie characters: Laurel was the industrious "idea man" while Hardy was more easygoing.

Catchphrases

The catchphrase most used by Laurel and Hardy on film is: "Well, here's another nice mess you've gotten me into!" The phrase was earlier used by W. S. Gilbert in both The Mikado from 1885 and The Grand Duke from 1896. It was first used by Hardy in The Laurel-Hardy Murder Case in 1930. In popular culture the catchphrase is often misquoted as "Well, here's another fine mess you've gotten me into." The misquoted version of the phrase was never used by Hardy and the misunderstanding stems from the title of their film Another Fine Mess.Numerous variations of the quote appeared on film. For example, in Chickens Come Home Ollie says impatiently to Stan "Well...." with Stan replying, "Here's another nice mess I've gotten you into." The films Thicker than Water and The Fixer-Uppers use the phrase "Well, here's another nice kettle of fish you pickled me in!" In Saps at Sea the phrase becomes "Well, here's another nice bucket of suds you've gotten me into!"Another regular catchphrase, cried out by Ollie in moments of distress or frustration, as Stan stands helplessly by, is "Why don't you do something to help me?" And another, not-as-often used catchphrase of Ollie, particularly after Stan has accidentally given a verbal idea to an adversary of theirs to torment them even more: "Why don't you keep your (big) mouth shut?!"

"D'oh!" was a catchphrase used by the mustachioed Scottish actor James Finlayson who appeared in 33 Laurel and Hardy films.[ The phrase, expressing surprise, impatience, or incredulity, was the inspiration for "D'oh!" as spoken by the actor Dan Castelleneta portraying the character Homer Simpson in the long-running animated comedy The Simpsons. Homer's first intentional use of "d'oh!" occurred in the Ullman short "Punching Bag" (1988).

Films

Laurel and Hardy appeared for the first time together in The Lucky Dog (1921).

Hal Roach was considered to be the most important person in the development of their film careers. He brought the team together and they worked for Hal Roach Studios for over 20 years.[Charley Rogers worked closely with the three men for many years and said, "It could not have happened if Laurel, Hardy and Roach had not met at the right place and the right time."[Their first "official" film together as a team was the 1927 film Putting Pants on Philip. The plot involves Laurel as Philip, a young Scots man newly arrived in the United States, in full kilted splendor, suffering mishaps involving the kilt. His uncle, played by Hardy, is shown trying to put trousers on him. Also, in 1927, the pair starred in The Battle of the Century, a lost but now found classic short, which involved over 3,000 cream pies.

Laurel and Hardy with Lupe Vélez in Hollywood Party (1934)

Although Hal Roach employed writers and directors such as H. M. Walker, Leo McCarey, James Parrott and James W. Horne on the Laurel and Hardy films, Laurel would rewrite entire sequences or scripts. He would also have the cast and crew improvise on the sound stage; he would then meticulously review the footage during the editing process.[ By 1929 Laurel was the head writer and it was reported that the writing sessions were gleefully chaotic. Stan had three or four writers who joined in a perpetual game of 'Can You Top This?' As Laurel obviously relished writing gags, Hardy was more than happy to leave the job to his partner and was once quoted as saying "After all, just doing the gags was hard enough work, especially if you have taken as many falls and been dumped in as many mudholes as I have. I think I earned my money". From this point, Laurel was an uncredited film director for their films. He ran the Laurel and Hardy set, no matter who was in the director's chair, but never felt compelled to assert his authority. Roach remarked: "Laurel bossed the production. With any director, if Laurel said 'I don't like this idea,' the director didn't say 'Well, you're going to do it anyway.' That was understood." As Laurel made so many suggestions there was not much left for the credited director to do.

Laurel and Hardy in the 1939 film The Flying Deuces

The first feature film starring Laurel and Hardy was Pardon Us from 1931.[ The following year The Music Box, whose plot revolved around the pair pushing a piano up a long flight of steps,[ won an Academy Award for Best Live Action Short Subject] While many enthusiasts claim the superiority of The Music Box, their 1929 silent film Big Business is by far the most consistently acclaimed. The plot of this film sees Laurel and Hardy as Christmas tree salesman involved in a classic tit-for-tat battle with a character played by James Finlayson that eventually destroys his house and their car Big Business was added to the National Film Registry in the United States as a national treasure in 1992. The film Sons of the Desert from 1933 is often claimed to be Laurel and Hardy's best feature-length film.A number of their films were reshot with Laurel and Hardy speaking in Spanish, Italian, French or German. The plots for these films were similar to the English-language version although the supporting cast were often native language speaking actors. While Laurel and Hardy could not speak these foreign languages they received voice coaching for their lines. The film Pardon Us from 1931 was re shot in all four foreign languages while the films Blotto, Hog Wild and Be Big! were made in French and Spanish versions. Night Owls was made in both Spanish and Italian and Below Zero along with Chickens Come Home were only made in Spanish.

Laurel and Hardy in their final film, Atoll K (1951)

In 1951, Laurel and Hardy made their final feature-length film together, Atoll K. This film was a French-Italian co-production directed by Leo Joannon, but was plagued by problems with language barriers, production issues, and the serious health issues of both Laurel and Hardy. During the filming, Hardy began to lose weight precipitously and developed an irregular heartbeat. Laurel was experiencing painful prostate complications as well. Critics were disappointed with the storyline, English dubbing and Laurel's sickly physical appearance in the film. The film was not a success and it brought an end to Laurel and Hardy's film careers.[ Most Laurel and Hardy films have survived and have not gone out of circulation permanently. Three of their 107 films are considered lost and have not been seen in their complete form since the 1930s. The silent film Hats Off from 1927 has vanished completely. The first half of the 1927 film Now I'll Tell One is lost and the second half has yet to be released on video. In the 1930 operatic Technicolor musical The Rogue Song, Laurel and Hardy appear in 10 sequences and only one of which is known to exist with the complete soundtrack.

Final years

Following the making of Atoll K, Laurel and Hardy took some months off, allowing Laurel to recuperate. Upon their return to the European stage in 1952, they undertook a well-received series of public appearances, performing a short sketch Laurel had written called "A Spot of Trouble". Hoping to repeat the success the following year Laurel wrote a routine entitled "Birds of a Feather". On September 9, 1953, their boat arrived in Cobh in the Republic of Ireland. Laurel recounted their reception:The love and affection we found that day at Cobh was simply unbelievable. There were hundreds of boats blowing whistles and mobs and mobs of people screaming on the docks. We just couldn't understand what it was all about. And then something happened that I can never forget. All the church bells in Cobh started to ring out our theme song "Dance of the Cuckoos" and Babe (Oliver Hardy) looked at me and we cried. I'll never forget that day. Never.While on tour of the British Isles in 1953, Stan and Babe appeared on radio in Ireland and on a live BBC television broadcast of the popular show Face the Music with host Henry Hall a week later. Unfortunately, these shows do not appear to have been preserved on record, tape or kinescope, but notes from the Face The Music television appearance have been recently discovered. According to the notes, Ollie informs Stan that the television program has an audience of six million and that host Henry Hall is "going to introduce us to them". To which Stan replies "That's going to take a long time, isn't it?"

Laurel and Hardy on NBC's This Is Your Life December 1, 1954

In 1956, while following his doctor's orders to improve his health due to a heart condition, Hardy lost over 100 pounds (45 kg; 7.1 st). However, he suffered several strokes that resulted in the loss of mobility and speech. Despite having a long and successful career, it was reported that Hardy's home was sold to help cover the cost of his medical expenses during this time. He died of a stroke on August 7, 1957, and longtime friend Bob Chatterton stated that Hardy weighed just 138 pounds (63 kg; 9.9 st) at the time of his death. Hardy was laid to rest at Pierce Brothers Valhalla Memorial Park, North Hollywood. Following Hardy's death, Laurel and Hardy's films were returned to movie theaters as clips of their work were featured in Robert Youngson's silent-film compilation The Golden Age of Comedy.

For the remaining eight years of his life, Stan Laurel refused to perform and even turned down Stanley Kramer's offer of a cameo in his landmark 1963 movie It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World.[85] In 1960, Laurel was given a special Academy Award for his contributions to film comedy but was unable to attend the ceremony, due to poor health, and actor Danny Kaye accepted the award for him. Despite not appearing onscreen after Hardy's death, Laurel did contribute gags to several comedy filmmakers. During this period most of his communication was in the form of written correspondence and he insisted on answering every fan letter personally. Late in life, he hosted visitors of the new generation of comedians and celebrities including Dick Cavett, Jerry Lewis, Peter Sellers, Marcel Marceau, and Dick Van Dyke.[ Laurel lived until 1965 and survived to see the duo's work rediscovered through television and classic film revivals. He died on February 23 in Santa Monica and is buried at Forest Lawn-Hollywood Hills in Los Angeles, California.