Joseph Frank "Buster" Keaton (October 4, 1895 – February 1, 1966) was an American actor, comedian, film director, producer, screenwriter, and stunt performer. He was best known for his silent films, in which his trademark was physical comedy with a consistently stoic, deadpan expression, earning him the nickname "The Great Stone Face."] Critic Roger Ebert wrote of Keaton's "extraordinary period from 1920 to 1929, [when] he worked without interruption on a series of films that make him, arguably, the greatest actor–director in the history of the movies".] His career declined afterward with a dispiriting loss of his artistic independence when he was hired by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and he descended into alcoholism, ruining his family life. He recovered in the 1940s, remarried, and revived his career to a degree as an honored comic performer for the rest of his life, earning an Academy Honorary Award in 1959.

Many of Keaton's films from the 1920s, such as Sherlock Jr. (1924), The General (1926), and The Cameraman (1928), remain highly regarded,[5] with the second of these three widely viewed as his masterpiece.] Among its strongest admirers was Orson Welles, who stated that The General was cinema's highest achievement in comedy, and perhaps the greatest film ever made. Keaton was recognized as the seventh-greatest film director by Entertainment Weekly, and in 1999, the American Film Institute ranked him the 21st greatest male star of classic Hollywood cinema

Keaton was born into a vaudeville family in Piqua, Kansas, the small town where his mother, Myra Keaton (née Cutler), was when she went into labor. He was named "Joseph" to continue a tradition on his father's side (he was sixth in a line bearing the name Joseph Keaton and "Frank" for his maternal grandfather, who disapproved of his parents' union. Later, Keaton changed his middle name to "Francis" His father was Joseph Hallie "Joe" Keaton, who owned a traveling show with Harry Houdini called the Mohawk Indian Medicine Company, which performed on stage and sold patent medicine on the side.[citation needed]

According to a frequently repeated story, which may be apocryphal, Keaton acquired the nickname "Buster" at about 18 months of age. Keaton told interviewer Fletcher Markle that Houdini was present one day when the young Keaton took a tumble down a long flight of stairs without injury. After the infant sat up and shook off his experience, Houdini remarked, "That was a real buster!" According to Keaton, in those days, the word "buster" was used to refer to a spill or a fall that had the potential to produce injury. After this, it was Keaton's father who began to use the nickname to refer to the youngster. Keaton retold the anecdote over the years, including a 1964 interview with the CBC's Telescope.

At the age of three, Keaton began performing with his parents in The Three Keatons. He first appeared on stage in 1899 in Wilmington, Delaware. The act was mainly a comedy sketch. Myra played the saxophone to one side, while Joe and Buster performed on center stage. The young Keaton would goad his father by disobeying him, and the elder Keaton would respond by throwing him against the scenery, into the orchestra pit, or even into the audience. A suitcase handle was sewn into Keaton's clothing to aid with the constant tossing. The act evolved as Keaton learned to take trick falls safely; he was rarely injured or bruised on stage. This knockabout style of comedy led to accusations of child abuse, and occasionally, arrest. However, Buster Keaton was always able to show the authorities that he had no bruises or broken bones. He was eventually billed as "The Little Boy Who Can't Be Damaged," with the overall act being advertised as "'The Roughest Act That Was Ever in the History of the Stage." Decades later, Keaton said that he was never hurt by his father and that the falls and physical comedy were a matter of proper technical execution. In 1914, Keaton told the Detroit News: "The secret is in landing limp and breaking the fall with a foot or a hand. It's a knack. I started so young that landing right is second nature with me. Several times I'd have been killed if I hadn't been able to land like a cat. Imitators of our act don't last long, because they can't stand the treatment.

Keaton claimed he was having so much fun that he would sometimes begin laughing as his father threw him across the stage. Noticing that this drew fewer laughs from the audience, he adopted his famous deadpan expression whenever he was working.

The act ran up against laws banning child performers in vaudeville. According to one biographer, Keaton was made to go to school while performing in New York, but only attended for part of one day. Despite tangles with the law and a disastrous tour of music halls in the United Kingdom, Keaton was a rising star in the theater. Keaton stated that he learned to read and write late, and was taught by his mother. By the time he was 21, his father's alcoholism threatened the reputation of the family act,[] so Keaton and his mother, Myra, left for New York, where Buster Keaton's career swiftly moved from vaudeville to film

Keaton served in the United States Army in France with the 40th Infantry Division during World War I. His unit remained intact and was not broken up to provide replacements, as happened to some other late-arriving divisions. During his time in uniform, he suffered an ear infection that permanently impaired his hearing.

Silent film era

Poster for Convict 13 (1920)

A clip from the beginning of Cops (1922)

In 1920, The Saphead was released, in which Keaton had his first starring role in a full-length feature. It was based on a successful play, The New Henrietta, which had already been filmed once, under the title The Lamb, with Douglas Fairbanks playing the lead. Fairbanks recommended Keaton to take the role for the remake five years later, since the film was to have a comic slant.

After Keaton's successful work with Arbuckle, Schenck gave him his own production unit, Buster Keaton Comedies. He made a series of two-reel comedies, including One Week (1920), The Playhouse (1921), Cops (1922), and The Electric House (1922). Keaton then moved to full-length features.

Keaton (center) in 1923, with (from left) writers Joe Mitchell, Clyde Bruckman, Jean Havez and Eddie Cline.

Roscoe Arbuckle, Keaton and Al St. John in 1918

It was an expensive misfire, and Keaton was never entrusted with total control over his films again. His distributor, United Artists, insisted on a production manager who monitored expenses and interfered with certain story elements. Keaton endured this treatment for two more feature films, and then exchanged his independent setup for employment at Hollywood's biggest studio, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM). Keaton's loss of independence as a filmmaker coincided with the coming of sound films (although he was interested in making the transition) and mounting personal problems, and his career in the early sound era was hurt as a result.

Use of parody

One of his most biting parodies is The Frozen North (1922), a satirical take on William S. Hart's Western melodramas, like Hell's Hinges (1916) and The Narrow Trail (1917). Keaton parodied the tired formula of the melodramatic transformation from bad guy to good guy, through which went Hart's character, known as "the good badman".[ He wears a small version of Hart's campaign hat from the Spanish–American War and a six-shooter on each thigh, and during the scene in which he shoots the neighbor and her husband, he reacts with thick glycerin tears, a trademark of Hart's. Audiences of the 1920s recognized the parody and thought the film hysterically funny. However, Hart himself was not amused by Keaton's antics, particularly the crying scene, and did not speak to Buster for two years after he had seen the film. The film's opening intertitles give it its mock-serious tone, and are taken from "The Shooting of Dan McGrew" by Robert W. Service.

In The Playhouse (1921), he parodied his contemporary Thomas H. Ince, Hart's producer, who indulged in over-crediting himself in his film productions. The short also featured the impression of a performing monkey which was likely derived from a co-biller's act (called Peter the Great). Three Ages (1923), his first feature-length film, is a parody of D. W. Griffith's Intolerance (1916), from which it replicates the three inter-cut shorts structure. Three Ages also featured parodies of Bible stories, like those of Samson and Daniel. Keaton directed the film, along with Edward F. Cline.

Sound era and television

With Charlotte Greenwood in one of his first "talkies", 1931's Parlor, Bedroom and Bath

Keaton was forced to use a stunt double during some of the more dangerous scenes, something he had never done in his heyday, as MGM wanted badly to protect its investment. "Stuntmen don't get laughs," Keaton had said. Some of his most financially successful films for the studio were during this period. MGM tried teaming the laconic Keaton with the rambunctious Jimmy Durante in a series of films, The Passionate Plumber, Speak Easily, and What! No Beer? The latter would be Keaton's last starring feature in his home country. The films proved popular. (Thirty years later, both Keaton and Durante had cameo roles in It's a Mad Mad Mad Mad World, albeit not in the same scenes.)

Keaton was so demoralized during the production of 1933's What! No Beer? that MGM fired him after the filming was complete, despite the film being a resounding hit. In 1934, Keaton accepted an offer to make an independent film in Paris, Le Roi des Champs-Élysées. During this period, he made another film, in England, The Invader (released in the United States as An Old Spanish Custom in 1936).

Educational Pictures

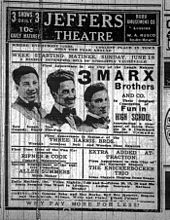

Upon Keaton's return to Hollywood, he made a screen comeback in a series of 16 two-reel comedies for Educational Pictures. Most of these are simple visual comedies, with many of the gags supplied by Keaton himself, often recycling ideas from his family vaudeville act and his earlier films.[36] The high point in the Educational series is Grand Slam Opera, featuring Buster in his own screenplay as an amateur-hour contestant. When the series lapsed in 1937, Keaton returned to MGM as a gag writer, including the Marx Brothers films At the Circus (1939) and Go West (1940), and providing material for Red Skelton.[37] He also helped and advised Lucille Ball in her comedic work in films and television.[38]Columbia Pictures

In 1939, Columbia Pictures hired Keaton to star in ten two-reel comedies, running for two years. The director was usually Jules White, whose emphasis on slapstick and farce made most of these films resemble White's Three Stooges comedies. Keaton's personal favorite was the series' debut entry, Pest from the West, a shorter, tighter remake of Keaton's little-viewed 1935 feature The Invader; it was directed not by White but by Del Lord, a veteran director for Mack Sennett. Moviegoers and exhibitors welcomed Keaton's Columbia comedies, proving that the comedian had not lost his appeal. However, taken as a whole, Keaton's Columbia shorts rank as the worst comedies he made, an assessment he concurred with in his autobiography.[ The final entry was She's Oil Mine, and Keaton swore he would never again "make another crummy two-reeler."1940s and feature films

Keaton's personal life had stabilized with his 1940 marriage, and now he was taking life a little easier, abandoning Columbia for the less strenuous field of feature films. Throughout the 1940s, Keaton played character roles in both "A" and "B" features. He made his last starring feature El Moderno Barba Azul (1946) in Mexico; the film was a low budget production, and it may not have been seen in the United States until its release on VHS in the 1980s, under the title Boom in the Moon. Critics rediscovered Keaton in 1949 and producers occasionally hired him for bigger "prestige" pictures. He had cameos in such films as In the Good Old Summertime (1949), Sunset Boulevard (1950), and Around the World in 80 Days (1956). In In The Good Old Summertime, Keaton personally directed the stars Judy Garland and Van Johnson in their first scene together where they bump into each other on the street. Keaton invented comedy bits where Johnson keeps trying to apologize to a seething Garland, but winds up messing up her hairdo and tearing her dress.Keaton also had a cameo as Jimmy, appearing near the end of the film It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963). Jimmy assists Spencer Tracy's character, Captain C. G. Culpepper, by readying Culpepper's ultimately-unused boat for his abortive escape. (The restored version of that film, released in 2013, contains a restored scene where Jimmy and Culpeper talk on the telephone. Lost after the comedy epic's "roadshow" exhibition, the audio of that scene was discovered, and combined with still pictures to recreate the scene.) Keaton was given more screen time in A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1966). The appearance, since it was released after his death, was his posthumous swansong.

Keaton also appeared in a comedy routine about two inept stage musicians in Charlie Chaplin's Limelight (1952), recalling the vaudeville of The Playhouse. With the exception of Seeing Stars, a minor publicity film produced in 1922, Limelight was the only time in which the two would ever appear together on film.

In 1949, comedian Ed Wynn invited Keaton to appear on his CBS Television comedy-variety show, The Ed Wynn Show, which was televised live on the West Coast. Kinescopes were made for distribution of the programs to other parts of the country since there was no transcontinental coaxial cable until September 1951.

1950s–1960s and television

Keaton feigning getting his foot stuck in railroad tracks at Knott's Berry Farm in 1956

In 1950, Keaton had a successful television series, The Buster Keaton Show, which was broadcast live on a local Los Angeles station. Life with Buster Keaton (1951), an attempt to recreate the first series on film and so allowing the program to be broadcast nationwide, was less well received. He also appeared in the early television series Faye Emerson's Wonderful Town. A theatrical feature film, The Misadventures of Buster Keaton, was fashioned from the series. Keaton said he canceled the filmed series himself because he was unable to create enough fresh material to produce a new show each week. Keaton also appeared on Ed Wynn's variety show. At the age of 55, he successfully recreated one of the stunts of his youth, in which he propped one foot onto a table, then swung the second foot up next to it, and held the awkward position in midair for a moment before crashing to the stage floor. I've Got a Secret host Garry Moore recalled, "I asked (Keaton) how he did all those falls, and he said, 'I'll show you'. He opened his jacket and he was all bruised. So that's how he did it—it hurt—but you had to care enough not to care."

Unlike his contemporary Harold Lloyd, who kept his films from being televised, Keaton's periodic television appearances helped to revive interest in his silent films in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1954, Keaton played his first television dramatic role in "The Awakening", an episode of the syndicated anthology series Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., Presents. About this time, he also appeared on NBC's The Martha Raye Show.

Keaton as a time traveler in a 1961 episode of The Twilight Zone, "Once Upon a Time"

With Joe E. Brown in the "Journey to Ninevah" episode of Route 66 from 1962

In December 1958, Keaton was a guest star as Charlie, a hospital janitor who provides gifts to sick children, in the episode "A Very Merry Christmas" of The Donna Reed Show on ABC. He returned to the program in 1965 in the episode "Now You See It, Now You Don't". The 1958 episode has been included in the DVD release of Donna Reed's television programs. One of the show's cast-members, Paul Peterson, recalled that Keaton "put together an incredible physical skit. His skills were amazing. I never saw anything like it before or since."

In August 1960, Keaton played mute King Sextimus the Silent in the national touring company of the Broadway musical Once Upon A Mattress. Eleanor Keaton was cast in the chorus. After a few days, Keaton warmed to the rest of the cast with his "utterly delicious sense of humor", according to Fritzi Burr, who played opposite him as his wife Queen Aggravain. When the tour landed in Los Angeles, Keaton invited the cast and crew to a spaghetti party at his Woodland Hills home, and entertained them by singing vaudeville songs.

In 1960, Keaton returned to MGM for the final time, playing a lion tamer in a 1960 adaptation of Mark Twain's The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Much of the film was shot on location on the Sacramento River, which doubled for the Mississippi River setting of Twain's original book.

In 1961, he starred in The Twilight Zone episode "Once Upon a Time", which included both silent and sound sequences. Keaton played time-traveler Mulligan, who traveled from 1890 to 1960, then back, by means of a special helmet.

In January 1962, he worked with comedian Ernie Kovacs on a television pilot tentatively titled "Medicine Man," shooting scenes for it on January 12, 1962—the day before Kovacs died in a car crash. "Medicine Man" was completed but not aired. It can, however, be viewed, under its alternate title A Pony For Chris on an Ernie Kovacs DVD set.

Keaton also found steady work as an actor in TV commercials, including a series of silent ads for Simon Pure Beer made in 1962 by Jim Mohr in Buffalo, New York in which he revisited some of the gags from his silent film days.

In 1964, Keaton appeared with Joan Blondell and Joe E. Brown in the final episode of The Greatest Show on Earth, a circus drama starring Jack Palance. In November, 1965, he appeared on the CBS television special A Salute To Stan Laurel which was a tribute to the late comedian (and friend of Keaton) who had died earlier that year. The program was produced as a benefit for the Motion Picture Relief Fund and featured a range of celebrities, including Dick Van Dyke, Danny Kaye, Phil Silvers, Gregory Peck, Cesar Romero, and Lucille Ball. In one segment, Ball and Keaton do a silent sketch on a park bench with the two clowns wrestling over an oversized newspaper, until a policeman (played by Harvey Korman) breaks up the fun. The skit called "A Day in the Park" was filmed and broadcast in color. It marked the only time Ball and Keaton worked together in front of a camera.

Keaton starred in four films for American International Pictures: 1964's Pajama Party and 1965's Beach Blanket Bingo, How to Stuff a Wild Bikini and Sergeant Deadhead. As he had done in the past, Keaton also provided gags for the four AIP films in which he appeared. Those films' director, William Asher, who cast Keaton, recalled,

I always loved Buster Keaton. I thought, what a wonderful person to look on and react to these young kids and to view them as the audience might, to shake his head at their crazy antics. ... He loved it. He would bring me bits and routines. He'd say, 'How about this?' and it would just be this wonderful, inventive stuff. A lot of the audience seemed to be seeing Buster for the first time. Once the kids in the cast became aware of who he was, they all respected him and were crazy about him. And the other comics who came in—Paul Lynde, Don Rickles, Buddy Hackett—they hit it off with him great.In 1965, Keaton starred in the short film The Railrodder for the National Film Board of Canada. Wearing his traditional pork pie hat, he travelled from one end of Canada to the other on a motorized handcar, performing gags similar to those in films he made 50 years before. The film is also notable for being Keaton's last silent screen performance. The Railrodder was made in tandem with a behind-the-scenes documentary about Keaton's life and times, called Buster Keaton Rides Again, also made for the National Film Board, which is twice the length of the short film.[51]

He played the central role in Samuel Beckett's Film (1965), directed by Alan Schneider; he had previously declined the role of Lucky in the first American stage production of Waiting for Godot, having found Beckett's writing baffling. Also in 1965, he traveled to Italy to play a role in Due Marines e un Generale, co-starring alongside the famous Italian comedian duo of Franco Franchi and Ciccio Ingrassia. In 1987 Italian singer-songwriters Claudio Lolli and Francesco Guccini wrote a song, "Keaton", about his work on that film.

Keaton's last commercial film appearance was in A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1966), which was filmed in Spain in September–November 1965. He amazed the cast and crew by doing many of his own stunts, although Thames Television said his increasingly ill health did force the use of a stunt double for some scenes. His final appearance on film was a 1965 safety film produced in Toronto, Canada, by the Construction Safety Associations of Ontario in collaboration with Perini, Ltd. (now Tutor Perini Corporation), The Scribe. Keaton plays a lowly janitor at a newspaper. He intercepts a request from the editor to visit a construction site adjacent to the newspaper headquarters to investigate possible safety violations. Keaton died shortly after completing the film

Personal life

Keaton with family in 1922

Influenced by her family, Talmadge decided not to have more children, and this led to the couple staying in separate bedrooms. Her financial extravagance (she would spend up to a third of his salary on clothes) was another factor in the breakdown of the marriage. Keaton dated actress Dorothy Sebastian beginning in the 1920s and Kathleen Key] in the early 1930s. After attempts at reconciliation, Talmadge divorced Keaton in 1932, taking his entire fortune and refusing to allow any contact between Keaton and his sons, whose last name she had changed to Talmadge. Keaton was reunited with them about a decade later when his older son turned 18. With the failure of his marriage and the loss of his independence as a filmmaker, Keaton lapsed into a period of alcoholism.

In 1926, Keaton spent $300,000 to build a 10,000-square-foot (930 m2) home in Beverly Hills designed by architect Gene Verge, Sr., which was later owned by James Mason and Cary Grant.Keaton's "Italian Villa" can be seen in Keaton's film Parlor, Bedroom and Bath. Keaton later said, "I took a lot of pratfalls to build that dump."

The house suffered approximately $10,000 worth of damage from a fire in the nursery and dining room in 1931. Keaton was not at home at the time, and his wife and children escaped unharmed, staying at the home of Tom Mix until the following morning.

Keaton was at one point briefly institutionalized; according to the TCM documentary So Funny it Hurt, Keaton escaped a straitjacket with tricks learned from Harry Houdini. In 1933, he married his nurse, Mae Scriven, during an alcoholic binge about which he afterwards claimed to remember nothing (Keaton himself later called that period an "alcoholic blackout"). Scriven herself would later claim that she didn't know Keaton's real first name until after the marriage. The singular event that triggered Scriven filing for divorce in 1935 was her finding Keaton with Leah Clampitt Sewell (libertine wife of millionaire Barton Sewell) on July 4 the same year in a hotel in Santa Barbara. When they divorced in 1936, it was again at great financial cost to Keaton

On May 29, 1940, Keaton married Eleanor Norris (July 29, 1918 – October 19, 1998), who was 23 years his junior. She has been credited by Jeffrey Vance with saving Keaton's life by stopping his heavy drinking and helping to salvage his career.[] The marriage lasted until his death. Between 1947 and 1954, they appeared regularly in the Cirque Medrano in Paris as a double act. She came to know his routines so well that she often participated in them on TV revivals.

Keaton's grave at Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Hollywood Hills

Death

Keaton died of lung cancer on February 1, 1966, aged 70, in Woodland Hills, California. Despite being diagnosed with cancer in January 1966, he was never told that he was terminally ill or that he had cancer; Keaton thought that he was recovering from a severe case of bronchitis. Confined to a hospital during his final days, Keaton was restless and paced the room endlessly, desiring to return home. In a British television documentary about his career, his widow Eleanor told producers of Thames Television that Keaton was up out of bed and moving around, and even played cards with friends who came to visit the day before he died. Keaton was interred at the Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery in Hollywood Hills, California.Influence and legacy

Keaton's star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame

Jacques Tati is described as "taking a page from Buster Keaton's playbook."[64]

A 1957 film biography, The Buster Keaton Story, starring Donald O'Connor as Keaton was released.] The screenplay, by Sidney Sheldon, who also directed the film, was loosely based on Keaton's life but contained many factual errors and merged his three wives into one character.[65] A 1987 documentary, Buster Keaton: A Hard Act to Follow, directed by Kevin Brownlow and David Gill, won two Emmy Awards.

The International Buster Keaton Society was founded on October 4, 1992 – Buster’s birthday. Dedicated to bringing greater public attention to Keaton’s life and work, the membership includes many individuals from the television and film industry: actors, producers, authors, artists, graphic novelists, musicians, and designers, as well as those who simply admire the magic of Buster Keaton. The Society’s nickname, the “Damfinos,” draws its name from a boat in Buster’s 1921 comedy, “The Boat.”

Keaton in costume c.1939, wearing his signature pork pie hat

Keaton's physical comedy is cited by Jackie Chan in his autobiography documentary Jackie Chan: My Story as being the primary source of inspiration for his own brand of self-deprecating physical comedy.

Comedian Richard Lewis stated that Keaton was his prime inspiration, and spoke of having a close friendship with Keaton's widow Eleanor. Lewis was particularly moved by the fact that Eleanor said his eyes looked like Keaton's.

At the time of Eleanor Keaton's death, she was working closely with film historian Jeffrey Vance to donate her papers and photographs to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. The book Buster Keaton Remembered, by Eleanor Keaton and Vance, published after her death, was favorably reviewed.

In 2012, Kino Lorber released The Ultimate Buster Keaton Collection, a 14-disc Blu-ray box set of Keaton's work, including 11 of his feature films.